As a teacher, I like to ask questions to my students to get them to think about what they are doing, as awareness is key to improvement and inhibiting bad habits. This could be “Where is the phrase leading to?”, or “What is the character here?”, but also questions about technique, such as “How do you play high notes without getting louder?”. The initial answer one hears to a question like this is: “I need to support”. But what does “support” mean? What does the student understand by the term and does it actually produce the desired effect?

What is support?

“Support” is a direction given by teachers and is often taken on by a student as a kind of mantra for flute playing, without question. But if the student doesn’t know what it is, is it useful? Or could it be setting up a bad habit? What we do in our bodies to manipulate the airstream is not visible and so relies on a certain amount of imagination and guess-work. When we hear the sound as being a bit floppy, or a high note doesn’t speak/drops in pitch, the instinct is to contract muscles, whether this may be in the lips or the abdominals. How many of us have heard the phrase, “Use your diaphragm!”, as if the diaphragm were an arm or leg that we could just directly move. In my experience, the result of the word “support” is often the student just squeezing their stomach or gripping the muscles as if doing some crunches. All that does, however, is create tension, squashing the sound and inhibiting the breath. Imagine grabbing a tube of toothpaste around the middle in order to get some toothpaste out. You won’t get a nice layer of toothpaste on your toothbrush, but rather a mess and a ruined tube. In terms of flute playing, when you grip the abdominal muscles tightly, you are inhibiting the movement of the ribs and reducing the potential for the volume of air you can inhale.

End-gaining

Obviously, there is good reasoning behind it. One can hear when the quality of a note is not good, but I believe it is important to be aware of the what and the why, before considering how. Alexander Technique talks of “end-gaining”, where people can obsess with how to directly fix something that they actually cause bad habits, rather than thinking of the means whereby, which is more often more indirect in approach. For example, when we play softly, we don’t want the note to drop in pitch, so many of us will tense the lips in an effort to angle the air upwards and increase the air speed, or squeeze the stomach to stop it relaxing and letting the sound flop. Whilst these efforts have good intentions, they are not helpful in understanding what is happening and why. It also sets up a series of bad habits. Too much tension in the lips inhibits the movement of the jaw (which is essential for flexibility of pitch) and squeezing the stomach inhibits full and free movement of the diaphragm and ribs, which leads to an increased effort to breathe and further tension in the body, which reduces resonance. It is a destructive cycle, which cannot be maintained for a long time, whether one is a professional or not. When we want to achieve a certain result and get it by whatever means necessary, it can be tempting to repeat this since it “worked”, but one has to be careful of the damaging effects it may have on the body. So, there might be another way worth exploring before muscling through it.

Connotations of the word support

The word support has been mistreated and misinterpreted over the years to the extent that people avoid it and it has become almost taboo. It can induce feelings of anxiety and stress in people who have had it shouted at them in their formative years of learning the flute! However, if we think of other examples of support, we might think differently about it when applying it to flute playing. For example, a well-supported team does their job well because everybody works together in harmony, thanks to their supportive supervisor. Providing emotional support to somebody helps them feel better through listening and understanding, not trying to “fix their problems”. Supporting somebody’s weight allows them to walk without pain by taking pressure off, or a well-supported building will stay up because the foundations are balanced and secure. I’m sure there are many more, but you can see that support is really more about balance and coordination. In the body, you are supported from the ground up. Your feet feel the ground and the pull of gravity, but you remain upright by a good coordination of the joints and muscles all the way up to the top of the spine. There are opposing forces: gravity pulling you down and the upward stretch of the spine where the skull rests in balance. If we didn’t have these opposing forces, we would either be collapsed on the floor, or we would be floating in space. So, when we allow ourselves to be in the middle of that, feeling grounded whilst simultaneously feeling poised with the full length of the torso not being compromised, we are supported. When I think of this, I feel a greater amount of space inside the body, which is dynamic and elastic. If you feel this nice stretch in all directions, your sound will open up tremendously, which is a nice added bonus!

Airstream as a guide

When our body is supported like this, we can allow everything to work together in perfect balance and it is essential not to compromise it. So, when we want to play softly, or play high notes without getting flat, one needs to understand why this happens and what needs to happen in order to prevent it. When you play a high note and it drops to a lower pitch, the air speed has simply dropped. It is important to maintain a fast air speed, but that does not mean immediately gripping the muscles. Without the flute, try allowing a breath to come in and then letting out a long hiss (as if saying a long “ssss”). Notice how you release the air. Did you have to think of the muscles when you did that? Or did they work by themselves? This is an example of giving the right sort of directions to your body. You can then blow out through the lips, feeling the same release of air.

Back to playing softly, as the amount of air reduces, even with good uniform air speed, the pitch will drop at the end and go flat. To avoid this, we can gradually angle the airstream forward and up by allowing the jaw/lower lip to move forward and up. You can blow on your hand to get a sense of how you do this. If you try this with a smiley embouchure, you will notice that the distance you can move the airstream up and down is significantly less. That is because the muscles have tightened to an extent that affects the muscles around the jaw, restricting free movement. It’s like trying to swing your arm freely when gripping the shoulder muscles. You can also blow with fast air and slower air on your hand, then do it again putting your other hand on your stomach. You can feel how the air is released.

Pitch control is something I have written more about in my book, which you might find interesting if you struggle with notes dropping in pitch.

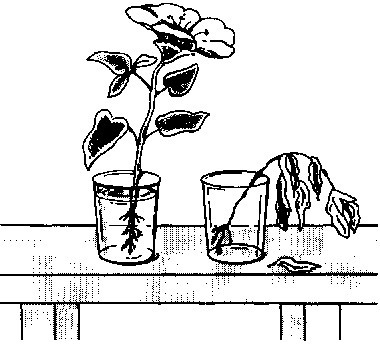

So by thinking of the speed and direction of your airstream and the release of air, you allow the body to do the work for you. A sound that is full of life is usually one where the air speed is just right and where the air is free and dynamic. Think of a plant that is watered and turgid versus a wilting plant. We can only produce a dynamic airstream when our bodies don’t get in the way of it. Let the airstream and your ears be your guide for finding solutions to technical hurdles.

When we stop “doing” and learn to just “undo”, we can find our natural support system and best coordination. Practice this well and you build good muscle memory, which is the basis of good technique. A good technique allows your expression to come through.

Thanks for reading and Happy Fluting!